The Message of the Christmas Bells

Many are familiar with the beautiful carol, I Heard the Bells on Christmas Day, but few know the tragedy from which the words were born.

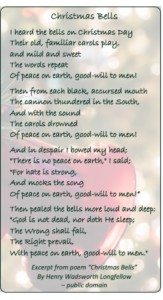

The carol originated as the poem, Christmas Bells. It was composed by the famous poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow following an extended season of loss and tragedy in his life.

Henry lost his first wife in childbirth. In July 1861, his second wife, Fanny, died tragically when her dress caught on fire. The burns Henry sustained trying to save his beloved wife scarred his face and shattered his spirit. He virtually stopped writing — turning his gifts instead to the translation of other literary works.

The bitter Civil War between North and South, which began just months before Fanny’s death, had already shaken Henry to the core. He was a strong abolitionist, recording his views in many journal entries like this one: “This dreadful stone of Slavery! — whenever you lift it, what reptiles crawl out from under it!”

The war raged on dividing the country and families and robbing many of loved ones. Although he was a man of deep faith, Henry could not shake his despair. On December 25, 1862, he penned in his journal: “ ‘A merry Christmas’ say the children, but that is no more for me.”

In March 1863, his eighteen-year-old son, Charles, ran off to join the Union army. Miraculously he survived camp fever in June but was seriously injured in battle in November. Henry made the journey from Massachusetts to Virginia to bring his son home for the long recuperation process.

We do not know where it started—perhaps the return of his son or the reminder of the church bells whose sound he had always loved. But that month proved to be a turning point for Henry. Despite his grief and the war still tearing the country apart, he found his hope rekindled—hope that the war against slavery would be won.

So as the church bells pealed out their joyful chimes on Christmas Day 1863, he again took pen to paper to capture his journey back to hope amid continuing suffering and loss. Millions around the world have found renewed hope through the message of his famous poem.

Now here we are in 2022 celebrating Hanukkah and Christmas—a season of light, hope and peace. Yet for many, the picture is eerily similar to Longfellow’s day. Human trafficking is a $150 billion business, racism is rampant, and wars continue to plague the world.

What a contrast to our relative affluence and comfort. We have so much, and yet desire more. Our wish lists grow so long; we seem oblivious to the needs of fellow humans. Clever commercials feed our appetites for more, better, brighter! And the fallout when our desires exceed reality? — Stress and depression!

But did you know there is a difference between wishing and hoping? Put simply, a wish is a desire for something often beyond our reach. A hope has an element of faith for something we are expecting but do not yet have—the kind of hope Longfellow held for the end of the war against slavery.

The difference is particularly relevant during this season. We may not be able to erase the travesty of war, poverty, racism, and human trafficking on our own. But there are simple, tangible actions we can all take with the resources we have to help restore hope in the world.

For example, we can:

- Speak up against the injustices around you.

- Send words of encouragement to someone going through a hard time.

“I’m so glad for every message you send. They give me hope that I am not alone.” - Contribute items to a food bank.

- Drop some change into the Christmas kettles.

- Donate to a humanitarian organization.

And when we find ourselves losing hope, perhaps we too can rekindle it through the message of the Christmas Bells.

“I’m full of faith, hope and good heart.” Henry Wadsworth Longfellow May 1864